Anyone looking up the history of LA in the 1920s will uncover incredible scandals, from C. C. Julian the get-rich-quick oil speculator, to “Sister” Aimee Semple McPherson, a Christian evangelist who faked her own kidnapping in order to spend time with a boyfriend. The San Fernando Valley, then mostly farmland with a few towns, was probably the quietest part of LA, but even it was not immune. The Valley Relics Postcard Collection contains three pieces related to these early scams.

The early ‘20s were the Valley’s period of transformation. At the time, it was called Los Angeles County’s “larder” or pantry, its farms producing a never-ending supply of fruit, nuts, vegetables, dairy products and fresh eggs. With LA’s oil and movie industries both booming, however, and fresh waves of migrants arriving every day, the sleepy, rural Valley was about to become the newest area of suburban development. The problem was that there were just too many newcomers for the older communities of Los Angeles to hold. They formed car camps on the outskirts of towns, which turned into new suburbs. And when they spilled over the hills, Valley land developers seized their opportunity. Glendale, for example, lured new settlers with the slogan “The Fastest Growing City in America.” But the boom of the 1920s also brought out the worst in some scheming developers, who took advantage of the situation to swindle land buyers. With LA so crowded, it was easy to believe that the Valley’s land was a resource that might soon run out!

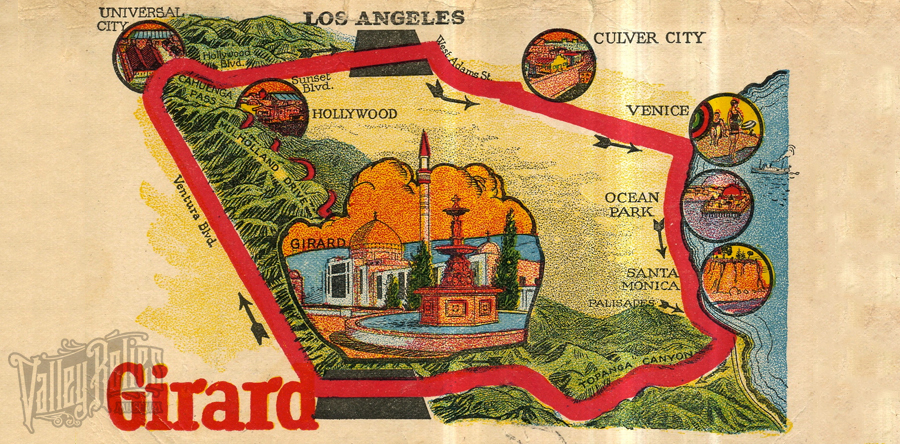

This postcard, dating from circa 1923, was a ticket for a free bus tour all around Los Angeles. It points out various stops: two luxurious hotels; Westlake Park (MacArthur Park today); the rich oil fields at Brea; the Santa Monica beaches. The “Soldiers Home” was the Sawtelle Veterans Hospital, a popular tourist attraction for its beauty, and the “LA Speedway” was a wooden-track racetrack and stadium. (The Speedway itself would soon fall victim to the land craze—it was torn down in 1924 and became the site of the Beverly Wilshire Hotel). Then the bus took its riders through the Cahuenga Pass to check out the Universal Studios lot (open to the public since the very beginning!) and on to the town of Girard.

What was Girard? Girard was a mirage, built by a “devious genius” who was born Victor Girard Kleinberger. When World War I made Germanic-sounding things unpopular, he dropped his last name and became Victor Girard. Girard had come to LA in an earlier boom period, in 1899, and had been making shady deals ever since. His first real estate empire had just crumbled in 1921, forcing him to declare bankruptcy. But Girard rebounded onto the Valley, buying up 2,886 acres in the southwestern region and planning a new development, which he named after himself.

This second postcard shows (in color) what Victor Girard wanted visitors to his land to see: an exotic “Turkish city,” complete with domes, minarets, and fountains. The mosque-like structures in the image were located at the intersection of Ventura Blvd. and Topanga Canyon Blvd., and were the offices of Girard’s “Boulevard Land Company.” But from all accounts, these buildings were the only ones with much of anything behind the front doors. The town of Girard was largely phony. Girard and his minions put false fronts on shacks to create the impression of a bustling, already-settled town where none existed. They planted 118,000 trees in just a few years to beautify the area. Tourists who picked up a postcard pass and arrived on the “sucker buses” were greeted by a well-oiled machine of salesmen, who took them up and down the tree-lined streets and tried to convince them how good an investment buying land in Girard would be.

Victor Girard was audacious in exploiting the population boom. “The Los Angeles District has shown a tremendous growth during the last few years,” he wrote, “and now that the world knows what we have here, the well known prediction of Mr. Harriman as to the destiny of Los Angeles will be rapidly brought to consummation.” Harriman, a wealthy railroad magnate, had predicted in the early 1900s that LA would one day be the largest city in the country. Accordingly, Girard painted a cramped vision of the future. He divided up his land into 6000 incredibly tiny lots, some only big enough to permit the building of a small cabin—when a more typical Valley lot size of the time was forty acres. The inhabitants of the town of Girard were expected to live in very close quarters with their neighbors! To maximize profits, the Boulevard Land Company also sold some tracts of land multiple times to different buyers, some allegedly over fifty times.

The Girard scheme reached its height in the mid-Twenties. For a time, it seemed to be on track to develop into a real town. It had a school, a newspaper, a fire department, and a nursery where the BLC grew its beloved trees. As the decade ended, however, Girard was hit with lawsuit after lawsuit as people discovered his fraud. The stock market crash of 1929 put the final nail in the coffin, and many of Girard’s first settlers simply packed up and moved somewhere else. Victor Girard himself seems to have abandoned the scheme by 1931, fleeing like a rat from a sinking ship. Only a few families held on through the Great Depression, and in 1941 the community reformed under a new name, inspired by the many trees: Woodland Hills.

Meanwhile, as Girard was getting off the ground in early 1923, two more schemers bought a 65-acre ranch in the Burbank area for $1000 an acre. But rather than a town, financiers John R. Osborne and C. C. Fitzpatrick were planning to build a cemetery. Over the next two years, they landscaped the area into a beautiful green park. No expense was spared: for example, the monumental entrance gate, which cost $140,000. Osborne and Fitzpatrick created an “up-to-date” look for the graves themselves by choosing flat plaques over traditional raised headstones. There were also three reflecting pools and a lovely fountain at the very center of the enclosure (pictured on the postcard above). Valhalla Memorial Park opened its gates with a dedication ceremony on March 1, 1925. Within five months, however, both of the owners were behind bars for gross fraud.

During the development phase from 1923-25, the Osborne-Fitzpatrick Finance Company and its sales team had been swindling their investors, who were mainly elderly people, with dire warnings. Los Angeles was running out of space, they told them. Their out-of-the-way land in the San Fernando Valley was one of the last remaining places to build a graveyard. And soon, they claimed, there would come a crisis: since a good part of the population boom was old, unhealthy people moving to California for the climate, where were they all going to go after they died? The scam victims either wanted to secure a grave for themselves (so as not to end up buried in a pile six corpses deep, as the lying financiers claimed might happen), or to gain a good investment that they could then resell when the cemetery “crisis” hit. Like Victor Girard, Osborne and Fitzpatrick also liked to make duplicate deeds to the same lot of land, selling one grave a total of sixteen times. By the time they were investigated and caught, they were both millionaires.

Surprisingly, while Fitzpatrick and Osborne served their time, Valhalla remained open for business. Members of Osborne’s family ran it, and the surrounding Valley land continued to develop and grow. The postcard in the museum’s collection may date from this somewhat peaceful period. In 1935, following the suicide of Osborne’s father, the property reverted to the state. In 1950, it was bought by the Pierce Brothers mortuary company, and still bears that name today. The monumental gate was closed (later to be turned into a memorial to early flight pioneers) and a new entrance built in North Hollywood.

The “boom” of the 1920s changed the Valley’s history forever. For a time, it seemed like its growth would never slow down, let alone stop. Con artists like Girard, Fitzpatrick and Osborne shamelessly exploited the boom in every possible way, from targeting the newly arrived “suckers” with free bus tours, to painting grim pictures of a Los Angeles that had run out of space to bury its dead. Today their scams are almost forgotten, with only a few relics remaining.

-Alison Turtledove

References:

- Cacioppo, Richard K. The History of Woodland Hills and Girard. Panorama City, CA: White Stone, Inc., 1982.

- Gaye, Laura B. Land of the West Valley. Encino, CA: Argold Press, 1975.

- Henstell, Bruce. Sunshine and Wealth: Los Angeles in the Twenties and Thirties. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1984.

- Mayers, Jackson. The San Fernando Valley. Walnut, CA: John D. MacIntyre, 1976.

- Meares, Hadley. “Valhalla Memorial Park and Portal of the Folded Wings: The Criminal Beginnings of a Burbank Burial Ground.” KCET Departures Column, Dec. 6, 2013. http://www.kcet.org/socal/departures/columns/graveyards-of-la/valhalla-memorial-park-and-the-portal-of-the-folded-wings-the-criminal-beginnings-of-a-burbank-buria.html

- McWilliams, Carey. Southern California: An Island on the Land. Layton, UT: Peregrine Smith Publications, 1983 (originally published 1946).

- Starr, Kevin. Material Dreams: Southern California through the 1920s. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.