In 1920 Ventura Boulevard was still a relatively unpopulated stretch of roadway. The long and narrow (no more than 14 feet in width) road was a difficult byway, particularly as it approached the Brant Rancho. Travelers from Los Angeles encountered a steep hill in which the road climbed and twisted and turned in an effort to ascend the great hill just west of present day Winnetka Avenue which was to later be referred to as Chalk Hill. The name derived from the fact that this hill contained not dirt, but nearly 100% pure magnesium chalk.

Until the 1920’s (prior to the arrival of the “Kaiser of Chalk Hill”) no one had ever lived on Chalk Hill , because most of the people were either farmers or livestock breeders and neither could survive on this mound of white powder.

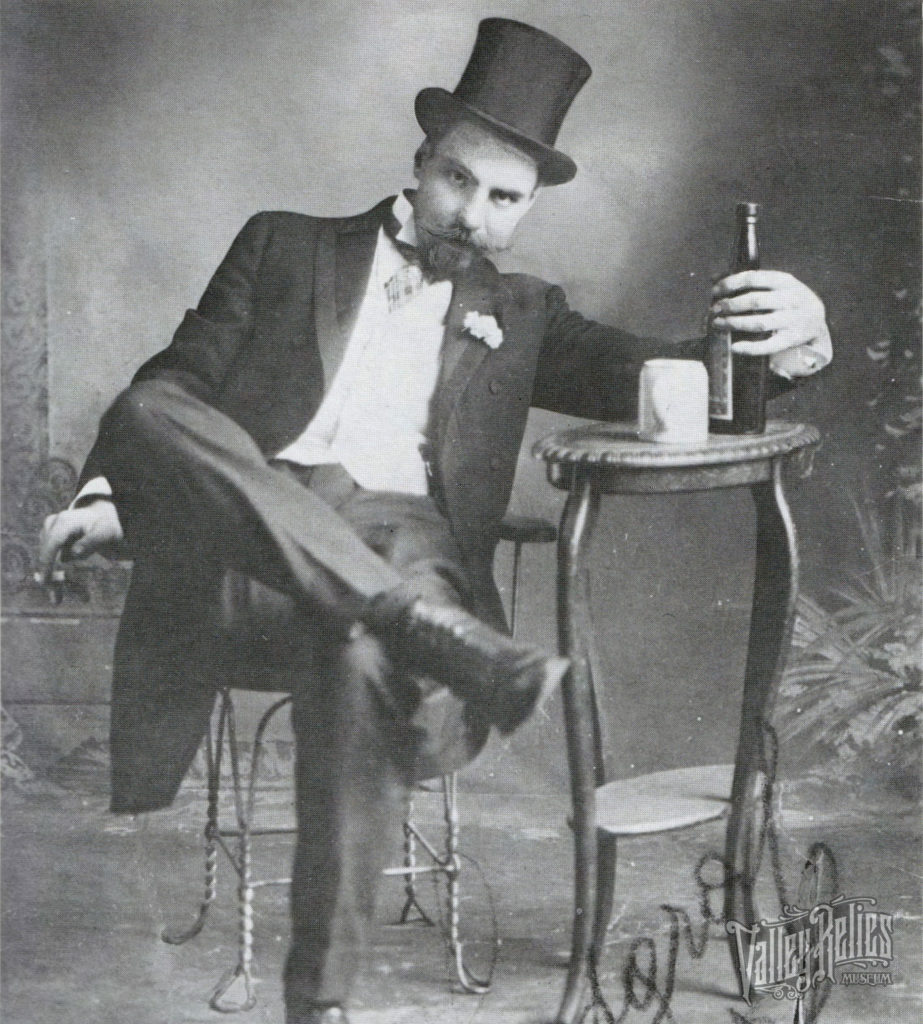

In 1922 Rudolph Francis Langraf purchased twelve acres on Chalk Hill. The tall six foot four inch Austrian with a small goatee and stubborn continental manners soon earned his nickname. Different from most of the farmers and eastern businessmen who lived in the San Fernando Valley in 1920, Langraf was born in California during the gold rush days but had spent much of his life in Austria.

For the next three decades, the Kaiser brought to Chalk Hill a unique identity, culture and charisma far different from his neighbors. Langraf and his five foot two inch wife, the former Mari Juch, operated a Chalk Hill rest stop and gas station for three decades. Known as the “Drinking Post,” it became the eastern gate for what was later to be known as Woodland Hills.

As an enterprising entrepreneur, Langraf developed many creative projects in succession. His first endeavor was to mine the chalk on his land, which was desirable as decorative field stone for the mansions of the wealthy of Los Angeles. The restaurant later to be called Rudy’s Place, and even later leased as a beer joint called the Hoofbeat, was a popular rendezvous for the weary travelers of 1920 California. Into the hill Langraf dug a fifty foot cave where he stored his wine, milk and eggs. In later years during prohibition the Kaiser would often sit in the cave with city officials, drinking and playing poker.

As an enterprising entrepreneur, Langraf developed many creative projects in succession. His first endeavor was to mine the chalk on his land, which was desirable as decorative field stone for the mansions of the wealthy of Los Angeles. The restaurant later to be called Rudy’s Place, and even later leased as a beer joint called the Hoofbeat, was a popular rendezvous for the weary travelers of 1920 California. Into the hill Langraf dug a fifty foot cave where he stored his wine, milk and eggs. In later years during prohibition the Kaiser would often sit in the cave with city officials, drinking and playing poker.

Langraf purchased great amounts of optical goods, microscopes and jewelry in Germany with the profits he made in the United States. Following World War I, the German “mark” was practically worthless and Langraf’s American money gave him great leverage. Several years later he put his optics to use when he installed over 35 mounted pairs of binoculars on Topanga Canyon Boulevard at the crest of the Santa Monica mountains. He also included several 6 foot telescopes, some of them as strong as two hundred power. This location served, as it does today, as a magnificent focal point for a view of the beautiful Valley of the Oaks. It was an ideal location since the coastal drive through Topanga Canyon Boulevard and back to Los Angeles via Ventura Boulevard was advertised as one of the city’s premier one day scenic adventures for the motor car set.

Travelers taking the scenic motor trip would leave early in the morning arriving at the halfway point, the top of Topanga, at about midday. For ten cents Langraf would allow them to gaze through one of his magnificent glasses. To increase interest, he had erected signs all over the Valley which could be read with his powerful glasses. On the top of Chalk Hill a mound of rock was put with little signs saying, “John Barleycorn is buried here.”

Despite his many enterprises, the Kaiser of Chalk Hill considered himself to be poor, compared to his western neighbor, John Henry Show. The Show estate was located at the western portion of what was to become Woodland Hills.

Credit: W.H.C.C